Are Parents with Shared Residence Happier? Children’s Postdivorce Residence Arrangements and Parents’ Life Satisfaction

Source: Stockholm Research Reports in Demography 2015: 17

Franciëlla van der Heijden, Utrecht University

Michael Gähler, SOFI, Stockholm University

Juho Härkönen, Department of Sociology, Stockholm University

Abstract:

This study investigates whether shared residence parents experience higher life satisfaction than sole and nonresident parents, and whether frequent visitation is similarly related to parents’ life satisfaction as shared residence. Regression analyses on data from 4,175 recently divorced parents show that shared residence parents report higher life satisfaction than other, particularly nonresident, parents, but that this relationship can largely be explained by benefits and opportunity costs of parenthood. Shared residence fathers enjoy a better relationship with their child and their ex-partner and are more engaged in leisure activities than nonresident fathers. Shared residence mothers are more involved in leisure activities, employment, and romantic relationships than sole resident mothers. These differences contribute to the shared residence parents’ higher life satisfaction. Frequent interaction between the nonresident father and the child could partly, but not completely, substitute for shared residence, increasing both nonresident fathers’ and sole mothers’ life satisfaction.

Keywords: Divorce, Joint physical custody, Life satisfaction, Living arrangements, Parents, Shared residence, Subjective well-being

Download the full report: http://www.suda.su.se/SRRD/SRRD_2015_17.pdf

Morality and Morals – Gay lobby faces schism

The Gay lobby Express has hit the metaphoric buffers. An ethical schism now exists for which they had not planned. The heat of the kitchen has hit home for homosexuals over matters the rest of us regard as mundane, if not unalterable. How will they cope ? If they are successful, will we ride in on their coat tails ? Will it yet prove a glimmer of hope ?

Finally, the same ethical dilemmas eternally faced by heterosexual couples regarding the conception and of child care have struck home in the homosexual community.

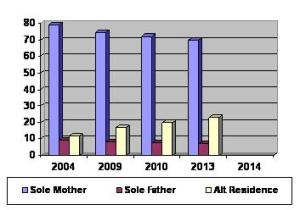

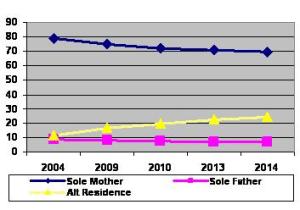

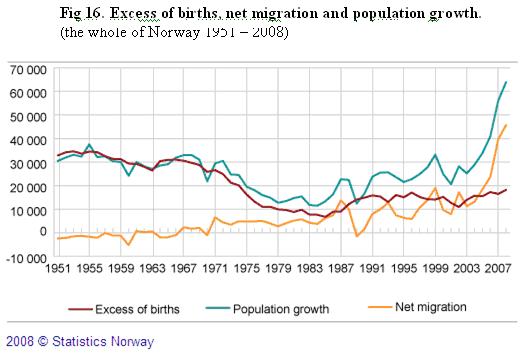

Though it is unclear at present if all wings of the LGBT feel the same way [1] a rupture was predictable and inevitable after so many years of presenting a united (if not slightly fraudulent), front to parliament and the public (see graph below and Annex 1).

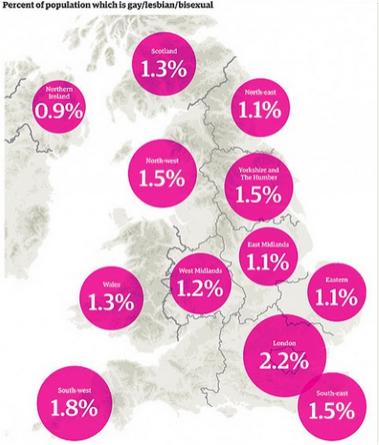

You might recall that in the parliamentary debates advocating gay unions its was stated that 10% of the UK population was gay and as such even visiting their partner in hospital was denied as  they were not ‘family’(see Annex 2). In the event K. Wellings et al 1994 assessment of 2% was confirmed by the ONS more than ten years after the passage of the Civil Partnership Act, i.e. the ONS also put the figure at 2% or less [2] (see also Annex 3).

they were not ‘family’(see Annex 2). In the event K. Wellings et al 1994 assessment of 2% was confirmed by the ONS more than ten years after the passage of the Civil Partnership Act, i.e. the ONS also put the figure at 2% or less [2] (see also Annex 3).

The present eruption within the homosexual community surrounds the news that music star Elton John has reacted angrily to comments by haute couture designers Dolce & Gabbana. In a magazine interview Dolce & Gabbana, made it clear that they viewed conception using IVF as artificial (which technically it is).

But they went further adding that they believe the only birth should be a traditional, natural birth. Reportedly in their interview with “TheBlaze”, Dolce said:

- “You are born to a mother and a father – or at least that’s how it should be. I call children of chemistry, synthetic children. Rented uterus, semen chosen from a catalogue.”

Dolce added; “I am gay, I cannot have a child. I guess you cannot have everything in life” and you can see his point. “Synthetic children” is perhaps too blunt a description but essentially it is true however it too could have been better finessed.

We all have to forego some things in life and realise as we mature that some of our adolescent ambitions will never be fulfilled and will lie forever dormant. Government has long promoted ‘responsible parenting’ and favoured a two parent arrangement (man and wife) even in the Blair era and even after separation.

Yet the ‘vox pop’ / straw poll reaction that television carries seems to be that if two men love each other enough and get married then the next thing they automatically want (and are in line for) is a family. But even for heterosexual couples a family is not guaranteed, hence the invention and adoption of IVF treatment for infertile couples. This is probably more a result of the ‘drip, drip effect’ (the effect of 30 years of social engineering), on the lower orders than any cultured or consider opinion by them.

Nevertheless it underlines that this area has long been a polarising trigger – a minefield – in society and now the LGBT have unconsciously strayed into that same minefield.

Heterosexual couples are under constant threat of losing their human ‘right’ option to cohabit on their own terms (with cohabiting couples likely to be treated as if spouses), while the homosexual community retains full rights to cohabit, have a civil union, or marry). No cohabiting homosexual couple will ever be threatened with being treated ‘as if married’ and lose much of their assets as looks likely for heterosexual couples. [3]

Even during the decade long debates – and there have been innumerable ones on TV and in parliament – the vocal minority of reformers have drowned out the homosexual majority who have no intention of wanting a partnership, or a marriage certificate, or the right to adopt children, or to become parents.

A national survey by ONS found that just over 45% of the gay community were cohabiting, and of the 1.5% only 8% of them lived in a household with at least one child present (see Annex 1).

How we got to this point owes a lot to the silent ‘social engineering’ warfare that has been an undeclared war against a blissfully unaware public. It is also the result of a long-term plan which involved the interplay of people (some with murky pasts) and an interweaving of questionable events. Such is the complexity – involving well-known figures – that there is only space for an elementary outline in Annex 4).

Virgin Territory

For a societal sub-set that is accustomed to seeing all things as black and white and other people’s opinions as totally either for or totally against them, this is new territory. So it is hardly surprising that Elton John responded to the Dolce & Gabbana comments by saying:

- “How dare you refer to my beautiful children as “synthetic”. And shame on you for wagging your judgmental little fingers at IVF – a miracle that has allowed legions of loving people, both straight and gay, to fulfil their dream of having children. Your archaic thinking is out of step with the times, just like your fashions. I shall never wear Dolce and Gabbana ever again.”

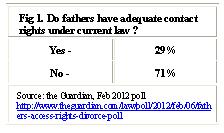

Sadly, ethical questions do not fall conveniently or comfortably into categories of either absolute saintliness or absolute wickedness. Politics makes strange bedfellows, and it is entirely reasonable to argue that this spat will, or could, result in a reappraisal of the roles of fathers and men in children’s lives. Something heterosexual father groups have being trying to get onto the public Agenda for many decades.

One wonders what the late Freddie Mercury, who was much beloved by both straight and gay alike, would have made of this spat ?

We have, since 1969, lost the value of stigma as a means of controlling aspects of society and in the same stampede have outlawed the ability to be judgmental which we all daily operate, whether we like it or not. Without some form of judgmentalism we become just an irrelevant lump of clay to be moulded into any shape by whoever is running society. Yet at the same time we are asked to be ‘liberal’ and ‘tolerant’ in all our views – but the moment we question liberalism or deviate from blanket tolerance a very illiberal and intolerant odium from officialdom descends upon us. [4]

Skewing numbers

Yes, in part Elton John is right, IVF has allowed many loving couples to fulfil their dream of having children – but most of those legions are straight and very few are gay. The process was always intended to serve heterosexual couples, not homosexuals who have simply commandeered it under an interpretation of Human Rights legislation (in much the same was as ‘the Pill’ was intended for married women to regulate family size – not for young single girls to engage in ‘recreational sex’).

Legislation since 2000 has overtly favoured the homosexual lobby and more than a decade on it is now (officially) recognised that a deal was done between Labour politicians in the mid 1990s and the LGBT lobby, e.g. Stonewall. [5]

By the late-1990s it was suspected by some that such a deal had been cut (with so many Gays in Blair’s cabinet it was the only rationale), but it has since been confirmed that in the years prior to the Labour government of 1997 it agreed to pass pro-LGBT legislation and legitimise homosexual practices and aims. [6] & [7].

One of those aims was to be seen as part of the ‘mainstream’; to be accepted as ‘normal.’ This was as process that began with declassification of homosexuality in the 1970s as a deviancy, aberration, or mental illness. This gave rise to misgivings among heterosexuals that they and their value systems were quietly under attack – and in part, though they were kept in the dark, they were proved right. [8]

For 10 years or more the seemingly ridiculous idea of 2 men being able to marry one another has been allowed to colonise our minds. During that process, time has allowed it to become less repugnant to a point where it is seen as an undeclared Human Right. It is at this juncture that life suddenly gets interesting. Regardless of the rights and wrongs of same-sex liaisons what was absolutely irrefutable was that custody disputes were historically seen as a straight-forward male/female issues for heterosexuals.

Scant regard was ever paid to “gender equality” save in its acceptance as a n ignored principle but since 2004 heterosexual couples no longer have the monopoly of custody battles. Battle will now be joined by homosexual couples who break up (and they break up at an alarming rate [9] (see Annex 5 and ‘Married but for all the wrong reasons.’ http://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/39/ ).

Being regarded as ‘normal’ and with sexual/gender equality overtones is something of an aberration in matrimonial terms (or should the word be ambiguous or incongruent?). Society has given special rights and protections to those people who enter into this covenant. There are prohibitions and penalties for having sexual intercourse with near relatives and outside the union. But same-sex unions cannot be dissolved because of any such infidelity (‘adultery’) by one of the parties. Is this then a marriage or a tax avoidance fig leaf ? (See Annex 6).

Gender Equality, as an issue, was (to translate it into plain English), a cause taken up by ‘women activists’ to keep mothers (i.e. women) in the welfare benefits driving seat and to always keep custody within their jurisdiction (and thus out of the hands of fathers).

For ‘women activists’ read ‘radical feminists and left wingers such as Patricia Hewitt MP and Harriet Harman MP (see both their careers as legal and equality ministries at Annex 4) who took things a little too far perhaps.

For ‘women activists’ read ‘radical feminists and left wingers such as Patricia Hewitt MP and Harriet Harman MP (see both their careers as legal and equality ministries at Annex 4) who took things a little too far perhaps.

Left: Harriet Harman and Patricia Hewitt, as they looked in the 1970s.

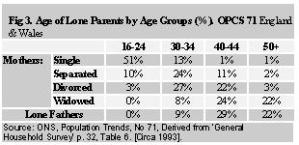

For ‘women activists’ read ‘radical feminists and left wingers such as Patricia Hewitt MP and Harriet Harman MP (see both their careers as legal and equality ministries at Annex 4) who took things a little too far perhaps. For them, and others in the Labour party in the 1970s, Gender Equality was seen as unlimited in scope. For example, in the 1997 election Hewitt praised lone parents of Leicester as ‘the heroes and heroines of my constituency [who] will be the heroes and heroines of the new Britain.’

Thus in the pursuit of this ‘new Britain’ they embraced, a wondrous array of what some might today call unhealthy ideas or fetishes – and none more so than paedophilia – with which both women were finally revealed as inextricably involved by national newspaper coverage in Feb & March 2014 (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paedophile_Information_Exchange ).

Silver lining ?

The question now will be how will this IVF matter be resolved for divorcing Gays ? Female homosexuals i.e. lesbians will argue over who is “mother” (not such a big deal there), while male homosexuals will have to argue the same but in front of courts which never give custody to a man.Will courts return the child to the egg donor ?

This is most unlikely. So courts will have to face up to awarding custody to a man and in the process will force a breaking of the mould for heterosexual fathers (or at least, one hopes that will be the path). [10]

Not only might heterosexual fathers who want to spend more time with their children (and who are presently prevented due to biased Gender Equality mantras) gain in this way from the impact homosexual ‘rights’ but it might even extend to forced adoption – should it ever arise in Gay relationships – over which heterosexual men have no influence.

Currently married or not, a father has little or no control over Social Workers’ decisions to abduct and permanently adopt a child (although society is slowly waking up to just scary and how scarring this is for both children and parents).

In the cases where Gay couples adopt a child further sanity can be envisaged. Their lobbying power within Whitehall, and government generally, will ensure forced adoption is unlikely and this benefit may trickle down to heterosexual fathers.

Majority ignored

Rising negative sentiments towards homosexuality peaked in 1987, the year before ‘Clause 28’ legislation was enacted. At the time the British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS), found that 75% of the population held that ‘homosexual activity’ was ‘always or mostly wrong’ (and only 11% believed it to be never wrong).

In 2007 a similar BSAS poll found that 61% of Conservative and 67% of Labour voters believed homosexual activity to be ‘always or mostly wrong’. By 2012, those figures stood at 28% and 47% respectively. Were these changes due to a more liberal stance adopted by the general public, or the product of re-education (which used to be called propaganda) ?

Whatever the cause, after the roll call of pro-homosexual legislation churned out almost annually on the Blair years an air of quiet resignation to the inevitable seems to have settled on with the general public (see Annex 7). They were not being listened to, so why expend any more energy on a cause the government had clearly made its mind up about ? It was time to move on to other battles and more important things.

Law of the unintended

Political hay was made when Teresa May cited an illegal immigrant who allegedly avoided deportation by the courts because he now had a ‘pet cat’ (BBC, 4 October 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-15160326 ). Whatever its truth it tapped into an unvocalised resentment, a sense of helplessness – plus a dislike in some quarters of the Establishment of the Human Rights Act.

Other stories followed including one published in the Daily Mail (16th April 2014) concerning another illegal immigrant, now aged 29, who had stabbed a 15-year-old schoolboy to death in 2001, less than a year after arriving in Britain. He could not then be deported because of his claim to be ‘gay’, and that if he were sent back to Jamaica he could face ‘degrading treatment’ for being homosexual that would breach his human rights. He was identified in court only as “JR” (to protect his anonymity ?). He was sent to jail in 2002 but was released in 2012 and is free to walk streets.

When change is made there is usually both good and the not-so-good that arise from it. Whatever one’s position on human rights, equality, diversity, etc, etc, society usually accommodates it, absorbs it, and gets on with its own life. In this case there is a faint possibility that further down the track that the changes made to accommodate homosexual demands might actually one day benefit desperately needed reform for heterosexual fathers.

Other changes to the social landscape will take time to be fully adopted and paternity leave for fathers is a prime candidate where the effects have yet to be worked through. An article appeared in ‘Children & Young People Now’ with the headline that “Only half of fathers take full paternity leave” (20 October 2009). http://www.cypnow.co.uk/bulletins/Daily-Bulletin/news/946912/?DCMP=EMC-DailyBulletin . We may well se that the gay community will accelerate the acceptance of paternity leave (paid or unpaid) for fathers.

This leads on to the questions surrounding employment and income for both straight and gay couples and between lesbians and gay couples. Differences based on gender between lesbians and homosexual men can be seen in literature on employment and income, e.g. Miles 200).

An analysis done by Blandford (2003), of the 1989 – 96 General Social Survey data indicated that both gender and sexual orientation had a bearing on earnings. The analysis reveals that, whilst gay men had a 30% –32% income disadvantage when compared to heterosexual peers, lesbians and bi-sexual women actually enjoyed an earnings advantage of 17% – 23%.

Another recent study of the incomes of same-sex cohabiting couples using Census data in the UK found gay men in this type of household earned 1% less than men living in equivalent heterosexual couples; but lesbian couples earned 35% more than women in heterosexual couples (Arabsheibani et al 2006).”

This, as Ivor Catt and I have explained many times over, is due to the propensity of commentators to unconsciously compare oranges with apples. Lesbians and homosexual men are for the main part single wage earners. As such they should only be compared with single men and single women. Earnings between single men and women have been at a parity long before the Equal Pay Acts (see Gilder and Amneus). It is only the married man who excels at wage generation (i.e. wealth creation). To compare single men and women (straight or gay) with married men is the oranges with apples analogy. Further, incomes of married women have always been lower than those of single men and women (straight or gay) and this has influenced the supposed “gender pay gap.”

This same 30% –32% alleged gap can be seen in Patricia Hewitt’s IPPR pamphlet “Social Justice, Children and Families” (pub. IPPR, 1993, page v), and, as mentioned before, in work by Gilder and Amneus.

E N D

Annex 1

How many people in Britain are gay, i.e. homosexual ?

For a long time the homosexual community fiercely decried the figure that they numbered only 2% in society as a woeful underestimate and questioned its validity. The figure came from a 1994 study by K Wellings et al., entitled ‘Sexual Behaviour in Britain’, (pub’d Penguin, see p.183).

This disbelief (of the 2%) was boosted by government estimates produced by the Treasury (circa 2004) for the anticipated of loss of ‘tax take’ from Inheritance Tax should same-sex marriage be legalised (it took until 2011 before the true figures were released – see below).

‘Gay Britain: inside the ONS statistics’,

Guardian, Sept 23rd 2011,

http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2010/sep/23/gay-britain-ons

In the past the tabloid press used a Treasury estimate (used in its planning for the Civil Partnership Act 2004), which assessed the figure to be between 5% to 7% – although the British crime survey had put it much lower 2.2%.

The Office for National Statistics published in 2011 the most comprehensive breakdown on the question. It survey 247,623.people across Britain – dwarfing even the mighty British crime survey, which ‘only’ asks 22,995 people.

Based on the ONS’ Integrated Household Survey the questioning involved showing people a card of options and asking them to indicate which category they fitted into. The ONS is highly confident of the technique and reliability of this method.

Extrapolated nationally, they suggest a population of 726,000 gay, lesbian or bisexual people in the UK which can be summarised in this way:

- Gay people are much more likely to be in managerial or professional occupations – 49% compared with 30% for straight workers

- Gay people are marginally better educated, with 38% holding a degree.

- Their age profile is also much younger than the rest of the population, with 66% under the age of 44 and 17% aged 16 to 24.

- Just over 45% of the gay community are cohabiting, although only 8% live in a household with at least one child present.

- A third of bisexual households include at least one child

- London is home to the highest concentration of gay people at 2.2% of the population, while this proportion falls to 0.9% in Northern Ireland

Annex 2

Parliamentary debates and advocating the number in the gay community

In the parliamentary debates advocating Gay unions (and in the press) it was frequently stated that 10% or more of the UK population was ‘gay’.

In the name of rectifying a series of injustices and human rights it was often cited that gay partners had no basic rights in the most mundane of activities. For example, this on Oct 12th 2004 from Chris Bryant MP :

- “ . . . . . When I was curate in High Wycombe, I used to visit patients in the local hospital It was not uncommon to meet people who had been prevented by the parents of their partner even from visiting the person whom they loved and had lived with for many years.” – Hansard, Column 226 [11]

In many respects the arguments used in Britain followed those of the 1997 Australian format during the debate on AMENDMENT (SEXUALITY DISCRIMINATION) BILL (Sept 17 1997).

- “ . . . . Of equal importance are the problems the partners of gay and lesbian people face. For example, access to their partners in hospitals when they are ill. In many situations, hospitals will not afford next of kin status to a same-sex partner, thus denying them visiting rights or the right to be consulted when making medical decisions. – See http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/hansard/hans35.nsf/c02fad1ff7f00ecbc82572e4002d0af9/f339f3227253a3d2482565fd00131195?OpenDocument&Click=

The BBC has conveniently listed most of the injustices that homosexual see as impairing their status from that of ‘normal’ people. The legal and technical flaws to the points made are enclosed in brackets:

- Inheritance tax – unlike couples within marriage, gay and lesbian partners currently pay up to 40% inheritance tax when inheriting from a partner. [NB However, if granted there would be no tax relief or taper for divorced parents (fathers) who wanted their children to inherit the same amount of assets. This would discriminate against one class of men. One avoidance measure for both categories is to set up a Trust – Ed].

- Rights on children – currently gay and lesbian partners do not find it easy to gain parental responsibility for each other’s children. [NB This is not unique to Gays. Many heterosexual fathers far from gaining ‘parental responsibility’ are actually legally shut out – Ed].

- Pension rights – under occupational schemes, heterosexuals can benefit from their dead spouses pensions. Though rights are enjoyed by gay and lesbian couples in some company schemes, many are excluded [NB Most UK pension schemes automatically guarantee payment for, say, 10 years payable to a named person after the recipient dies. So it’s a moot point – Ed].

- Next of kin – currently gay and lesbian partners do not have recognised rights as next of kin to authorise hospital treatment or to make funeral arrangements. [NB This is more true in its breach than in its application. Where it still existed only an amendment to internal regulations would be needed – Ed].

- Relationship breakdown – currently, gay and lesbian partners have weaker rights on things like shared homes where relationships break down [NB. This would indicate that they had been let down by the legal profession since shared homes are common among heterosexuals (e.g. shared ownership) who take the proper precautions – Ed].

- Benefit rights – gay and lesbian couples are currently assessed individually for state benefits. The bill will lead to joint assessment in some areas. It will also give gays and lesbians eligibility to survivor pensions and, where relevant, bereavement benefits [NB Benefits paid to 2 individual claimants are invariably greater than those paid to a married couple e.g. state pensions. Gays would lose some incomes as they would no longer be assessed as ‘living apart together’ (LAT) – Ed].

Source: “Legal rights currently denied homosexual couples” http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/bbc_parliament/3996035.stm

Annex 3

ONS also put the figure at 2% or less

Civil Partnership Act 2004 legitimised unions between same-sex couples – these are sometimes referred to as civil unions or same-sex unions.

Much, if not all of the reform introduced to accommodate homosexual wishes, was premised on the assumption – indeed, the claim – that homosexuals and lesbians comprised at least 10% of the British population. Indeed, ‘Stonewall’s’ Ben Summerskill put the figure at 20% in 1999 and the media especially left leaning newspapers, e.g. the ‘Observer’, often repeated the 20% figure well after 2005.

Politicians were for several decades under the psychological cosh not only of powerful national newspapers that were able to set agendas and massage reactions but also lobby groups such as Stonewall who were able to marshal street marches and protests.

Finally, in 2010 the Office for National Statistics (ONS) became involved in the collection of data about homosexual numbers. But far from 20% they found that only 1.5% of the population considered themselves gay or lesbian (i.e. 480,000) and 245,000 (0.5%) considered themselves bi-sexual. (Ref: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-11398629). A further 0.5% self-identified as “other”, and 3% responded as “do not know” or refused to answer.

It is surprising that all major political parties should find so attractive the combined voter Bloc for gays and lesbian (0.5 million) when it falls far short of the 1.6 million divorced fathers. See also http://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/39/

Annex 4

Social engineering today is a universally, well-understood term and tool for altering public perceptions but 20, or even 30, years ago it was a dark art and virtually unknown to the public (and one could liken it to a silent, black propaganda).

Re-engineering social values has, since its inception in the early 1980s, been in the hands of a select few. Gender Equality is one obvious candidate of this agenda which has enjoyed the quiet support of the powerful and influential.

Both Patricia Hewitt MP and Harriet Harman MP are household names from their terms in Blair’s Labour government. But there is a linkage between these and other politicians with not only the repugnant Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE) but also the Angry Brigade terrorist group of the 1970s which blew up cabinet minister’s houses, e.g. Robert Carr. Angela Mason (aka Angela Weir) was one of those Angry Brigade linkages.

The Blair government saw the creation of the Women Unit (aka Minister for Women and Equalities) and Angela Mason was, from 2003 to 2007, its director with a salary unprecedented in those days of £80,000 pa. [12] Before and after these dates it is on the public records that she advised government Depts on equality, i.e. gay and lesbian, matters.

After her trial for terrorism for which she was surprisingly found not guilty The Observer records that Angela Mason worked “as a lawyer for Camden Council in London”, yet her degrees are listed as History with a master’s degree in Sociology. Her only listed Law Degree is an honorary one given her in 2007 by Royal Holloway College – a college where Betsy Stanko who advises the Met Police on DV, is an Honorary Professor of Criminology (Prof Stanko claims to have created “the novel project on hate crime” yet this is merely, like her, an American import [13]).

Wheels within wheels ?

Judges and politicians should be seen to be beyond reproach but a look at the catalogue of ministers in that era questions the wisdom of appointing Angela Mason – and by whom ? [14]

All of the above and listed in the Table (right) could be described as radical feminists and/or left-wingers and all blocked attempts to gain parity for men and fathers. But this is to exclude other key players who were equally effective in their own right. If we take just one, Baroness Scotland, she worked at the Lord Chancellor’s Department (now the Justice Dept) from 2001-03; and in the Home Office from 2003-07; and was the Attorney General from 2007-10. As such she was able, and did, block any funding applications from voluntary fathers groups or alter custody laws in their favour, or recognise that annually 30% of all DV victims were in fact male (black and white).

All of the above and listed in the Table (right) could be described as radical feminists and/or left-wingers and all blocked attempts to gain parity for men and fathers. But this is to exclude other key players who were equally effective in their own right. If we take just one, Baroness Scotland, she worked at the Lord Chancellor’s Department (now the Justice Dept) from 2001-03; and in the Home Office from 2003-07; and was the Attorney General from 2007-10. As such she was able, and did, block any funding applications from voluntary fathers groups or alter custody laws in their favour, or recognise that annually 30% of all DV victims were in fact male (black and white).

The backgrounds of former minister Margaret Hodge MP also bears scrutiny. She was Islington’s council leader from 1982 to 1992 (adjacent to Camden – where Angela Mason worked); and was made Minister for Children in 2003. Islington council’s trendy liberal attitude and ‘equal  opportunities’ rules, allowed employees who declared themselves ‘gay’ to be exempted from intrusive background checks which could have prevented paedophiles from working in its children’s homes. [15]

opportunities’ rules, allowed employees who declared themselves ‘gay’ to be exempted from intrusive background checks which could have prevented paedophiles from working in its children’s homes. [15]

Left: Margaret Hodge MP

Yet when at Islington she ignored warnings that a paedophile network had been sexually abusing vulnerable children in every one of the council’s children’s homes since the 1970s. When proven in court, in Nov 2003, her public response was:

- “ . . . All that happened when we didn’t really understand child abuse in the way that we understand it now. This was the early 90s … It was only beginning to emerge that paedophiles were working with children, in children’s homes and elsewhere, . . .. “

Yet, as we know from Patricia Hewitt and Harriet Harman, paedophilia as a life style choice was well-known to exist in liberal and left-leaning circles and to have had (so it is alleged) government funding. [16]

Any sense of dishonour and impropriety failed to cross her mind and despite a prolonged public outcry she, the daughter of a multi-millionaire, did not stand down and instead 2003 saw her appointed by Blair as Britain’s first ‘Children’s Minister.’

As such she set up, in 2004, the National Children’s Database, known officially as ContactPoint. This government database held intrusive information on all children in England under the age of 18. ContactPoint (NCD) was intended to improve child protection by recording information about children and shared it between hundreds of Social Services Depts. (inc. 150 local authorities, and it was accessible by at least 330,000 users). The threat of it being “hacked” lead it to be referred to unofficially as the Meat Rack, as it was feared paedophiles could use it to select their next targets. The whole system was scrapped by a new Gov’t in 2010 after having cost cost £224m to set up, and £41m a year to run.

Another radicalised ‘direct action’ advocate was Peter Hain, who later became an MP and government minister. He faced trial in 1972 for Criminal Conspiracy as the Young Liberal Leader (stemming from his anti-apartheid stance and actions) and was found guilty. Apparently in 1972 a letter bomb was sent to him (it failed to explode because of faulty wiring). And puzzlingly he was then put on trial in 1974 for a bank robbery but was acquitted. [17] He has claimed that it was a ‘frame-up’ by the South African Bureau of State Security (BOSS) but the main witnesses were 3 schoolboys (! ?).

Some of today’s front bench politicians were directly and/or indirectly involved in radical groups and participated in or fermented unrest and violence at that time. Not just Peter Hain but Jack Straw MP, both former Blair Ministers but also Kim Howells MP (also a minister of state), and Lord Triesman, who started life as plain David Triesman are easily traceable.

Kim Howells is a former student radical and Communist union official who later converted to Blairism. In that role he found himself defending Britain’s intelligence services more unreservedly than the head of MI5.

As for Lord Triesman (aka David Triesman), he was once a radical left-wing student leader. After breaking up a meeting addressed by a defence industry scientist he was suspended from Essex University in 1968 for his radicalism and anti-establishment actions. He resigned from the  Labour Party and like Howells joined the Communist Party in 1970 (later rejoining the Labour party in 1977).

Labour Party and like Howells joined the Communist Party in 1970 (later rejoining the Labour party in 1977).

Right: Now moving in loftier circles, Lord Triesman (left) with Prince William, future King of England.

It was his Essex University activities where he rubbed shoulders with anarchists and brought him into contact with Anna Mendleson and Hilary Creek – the only women of the Angry Brigade to actually be convicted. Later, while on his path to becoming General Secretary of the Labour Party he helped organise street rioting during his salad days. And in true turncoat style he became General Secretary of the Association of University Teachers from 1993 to 2001. From 2008 (until 2010) he was chairman of both the FA and Britain’s bid to host the 2018 Olympic.

Annex 5

The desire to be seen as normal and absorbed into the mainstream of society is a two-edged sword. Homosexual couples who break up will now have to battle, as do heterosexuals, with lawyers costs, loss of income, confiscation of assets and fights over custody.

Although “Pink News” (22nd Feb 2006) puts a gloss on matters relating to the level of matrimony, absent is any mention of divorce and separation.

- “In total 3,648 couples formed civil partnerships in England & Wales between 21 Dec 2005 and 31 Jan 2006. Male partnerships are more popular (2,150 ceremonies) than women’s (1,138). – “Three and a half thousand English gay couples tie the knot”. Pink News, 22 Feb 2006.

(See also 1. ‘Married but for all the wrong reasons’, http://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/39/ , 2. “Same-sex marriages – Canada’s hidden data” https://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/08/13/43/ , and 3. “Gay Marriage & Unions – an Inter-European Comparison” https://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/06/10/41/ ).

However by 2010 the picture had changed in that more women were having civil partnerships – a trend noticed in other countries which had adopted a relaxed regime concerning same-sex marriage

However by 2010 the picture had changed in that more women were having civil partnerships – a trend noticed in other countries which had adopted a relaxed regime concerning same-sex marriage

- “Some 6,385 Civil Partnerships were conducted in Britain in 2010, 49% were men.” More women than men having civil partnerships”, Pink News. 7 July 2011.

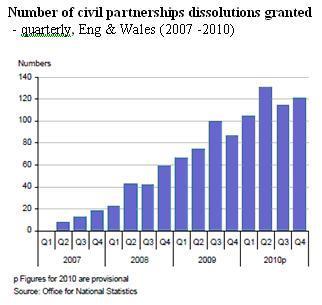

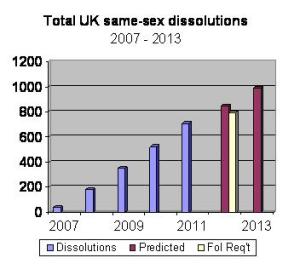

Between those two dates 2006 and 2011 the number of civil dissolutions (i.e. divorces) rose year by year (see ONS Table for 2007 – 10, right).

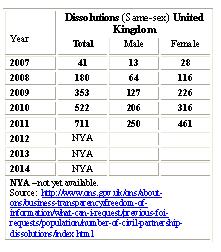

More recent data for the whole of the UK is for some reason not available from the ONS (see Table below). We might speculate it would show a continuing rise in the number of gay divorces. So with no new data forthcoming a gap exists post-2011 and so in light of this an extrapolation has been made (see graph below for 2007 – 13 marked ‘Predicted’ years).

More recent data for the whole of the UK is for some reason not available from the ONS (see Table below). We might speculate it would show a continuing rise in the number of gay divorces. So with no new data forthcoming a gap exists post-2011 and so in light of this an extrapolation has been made (see graph below for 2007 – 13 marked ‘Predicted’ years).

Fortunately, some data for the missing years has been found via a Freedom of Information request and the graph above has incorporated the additional year of data. Under “Number of civil partnership dissolutions in England and Wales 2010 – 2012” it shows the following: [18] Information from this FoI request has been added for 2012 and is shown in Yellow. However caution must be exercised as one total (711) is the for UK as a whole and one (provisionally 794) for only England & Wales. If this is later confirmed then the Total UK including Scotland and Ulster will exceed 794.

Fortunately, some data for the missing years has been found via a Freedom of Information request and the graph above has incorporated the additional year of data. Under “Number of civil partnership dissolutions in England and Wales 2010 – 2012” it shows the following: [18] Information from this FoI request has been added for 2012 and is shown in Yellow. However caution must be exercised as one total (711) is the for UK as a whole and one (provisionally 794) for only England & Wales. If this is later confirmed then the Total UK including Scotland and Ulster will exceed 794.

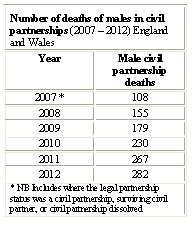

The same URL (see Footnote) also reveals the number of deaths (widowships) in the longer period of 2007 to 2012, see below:

Finally, there has been a noticeable swing or surplantation in Gay marriages / unions with an increasing number of lesbian unions.

Finally, there has been a noticeable swing or surplantation in Gay marriages / unions with an increasing number of lesbian unions.  This trend is also echoed in the number of lesbian dissolutions from 28 to 461 in 2011 (see Table above). It would appear that after the initial fillip of being able to exercise their legal and equality rights homosexual men have retrenched from formal unions. It would also appear that the Christian Institute’s prediction of inherent instability in same-sex relationships (7th May 2002) might be borne out.

This trend is also echoed in the number of lesbian dissolutions from 28 to 461 in 2011 (see Table above). It would appear that after the initial fillip of being able to exercise their legal and equality rights homosexual men have retrenched from formal unions. It would also appear that the Christian Institute’s prediction of inherent instability in same-sex relationships (7th May 2002) might be borne out.

The rate at which lesbian unions fall apart, i.e. through lesbian dissolutions, will be important to watch as they are, on balance, more likely to acquire children during the liaison or to already have children from a previous (perhaps heterosexual) marriage.

Sweden has been ahead of many countries in civil partnerships, so although the following information from “Gay Marriage Statistics” is now somewhat dated it is not obsolete, and it does indicate what the rest of Europe can expect as it catches up.

- “Gay men were 50% more likely to divorce within eight years and lesbian couples 167% more likely to divorce than heterosexual couples. In the Netherlands, between April 2001, when gay marriage was legalised, and December 2003 there were 5,751 gay marriages and 63 divorces.”

According to a report of the Institute for Marriage and Public Policy (IMAPP) and again based on data from around 2004, divorce rates among same-sex couples are confirmed as very high:

- “Gay male couples were 50% more likely to divorce within an 8-year period than were heterosexuals. Lesbian couples were 167% more likely to divorce than heterosexual couples. According to statistics released by the Dutch Government in 2005, the divorce rate of gay and lesbians couples in the Netherlands is nearly identical to that of heterosexual couples.”

But perhaps more significantly for the future IMAPP reports:

- “Even among childless households, same-sex male partnerships experienced almost a 50% higher likelihood (1.49 times as likely) of divorce during the study period, while childless lesbian couples were three times as likely (200% higher likelihood) to break up as a married couple without children.”

The authors of this study on short-term same-sex registered partnerships in Norway and Sweden cited that this may be due to same-sex couples’ ” . . . . non-involvement in joint parenthood”, “lower exposure to normative pressure about the necessity of life-long unions” as well as differing motivations for getting married.

Annex 6

Tax avoidance vehicle ?

Since the dawn of time societies have always afforded protection and a privileged status that extended into the present Christian era. But all that came to an abrupt end in the western world in 1970.

One of the encouragements offered to citizens who settled down and married and thus became positive contributors to society and wealth creation was the ability to mitigate penalties of asset and wealth transfer to children of that marriage upon one of the spouses’ death.

This concession discriminated against single heterosexual (unmarried) men and divorced fathers in particular since the latter groups had already been taxed at the time of their divorce (ancillary relief) and at death their estate stood to be taxed a second time by means of Inheritance Tax. At least the single heterosexual man would not have lost 90% of his asset wealth in a divorce.

Such is the tax relief now extended to same-sex couples (see Annex 2 above) that if one were cynical for a moment one could devise a tax avoidance vehicle for divorced fathers (and unmarried heterosexual men) simply by advocating their nominal marriage with another divorced father (see Part 1 of Schedule 1, below). In so doing, each surviving head of family household would be better able pass on their accumulated wealth to their children.

Alan Milburn, a former Labour minister for Health, when advised of the notion that “The engine of wealth creation is the married man” was completely non-plussed (CSJ fringe meeting Manchester, Sept 2013).

Divorcing same-sex couples may yet face the same level of assets confiscation in the future that their heterosexual brethren already endure.

Baroness O’Cathain made some excellent points in a house of lords debate (24 June 2004) in which she highlighted some of the resulting discrimination and inequalities the proposed Same-Sex Partnership bill would create (see http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/2004/jun/24/civil-partnership-bill-hl ).

- If a daughter gives up her job to look after her elderly mother for 20 years, should she be denied the same rights, including the financial benefits, which the Bill gives to same-sex couples?

- If a niece goes to live with her disabled aunt and looks after her for 15 years, is her love and commitment for her close relation considered to be less important than that of a same-sex couple?

- The niece has to pay inheritance tax if she inherits her aunt’s estate, but the survivor of a same-sex couple in a registered partnership would not. Is this situation fair and just? I think not.

Family members are currently broadly in the same position as same-sex couples regarding the succession of a tenancy. But it is important to remember that close relations are not exempt from Inheritance Tax and Capital Gains Tax.

- When the noble Lord, Lord Alli, spoke in support of a Bill introduced by the noble Lord, Lord Lester, inheritance tax was the first issue that he raised. He read from a letter written by the partner of Lord Montague of Oxford for whom the issue of inheritance tax was critical. The noble Lord, Lord Alli, told us that Lord Montague had to sell his possessions to pay the inheritance tax and said: Surely this cannot be right. It is unfair to make people sell their family homes”.—[Official Report, 25/1/02; col. 1697.]

It may come as a shock to parliamentarians living in their Westminster Bubble but if the ‘ordinary Joe’ citizen, who might own a corner shop, suddenly dies or has to retire due to a heart attack the Inland Revenue have long been able to pounce and demand huge sums due to Capital Gains Tax legislation. This has cost families not only the businesses which they have built up but all their savings, and even the homes they lived in. Lord Alli is right to think that Capital Gains Tax is unfair and pernicious but why limit the relief from it to the landed gentry ?

Baroness O’Cathain concluded by saying that the Bill provided people in same-sex relationships who went through a civil partnership to obtain many more rights than those in family relationships. In other words she believed that the same-sex couples Bill would give such partnership a higher status than (heterosexual) family relationships.

Echoing some of her points Lord Tebbit was of the view that as the Bill was presently drafted it discriminated against family members who are listed in Part 1 of Schedule 1 (i.e. partnership must not be within the prohibited degrees of relationship, e.g. niece and elderly aunt), and it discriminates by prohibiting the option of civil partnerships to persons of opposite sex. No adequate reason has been given for that. (see 24 June 2004, vol 662 cc1354-91 http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/2004/jun/24/civil-partnership-bill-hl).

- I believe that it is completely wrong. I believe that it is wrong when parents and children are excluded. I find it hard to see that the bonds by which they are united are weaker than those which may band homosexual couples, or indeed other couples of the same sex

Knowing of the new liberty to source overseas same-sex brides /partners it is surprising no one raised the question of the implications on the number of immigrants this law change might encourage.

Earlier in the same year (22nd April 2004) Baroness O’Cathain spoke of the government’s estimate that “ . . .. between 5% and 10% of homosexual couples would want to get involved in civil partnerships” with which she took issue:

- According to footnote 3 on page 108 of the Explanatory Notes to the Bill, the figure is 3.3%. That means that 96.7% of homosexuals in the UK will not register a civil partnership, in the Government’s own estimation.

- How can we justify spending all this parliamentary time on a Bill containing 196 clauses and 22 schedules, lasting 258 pages, which will take eight days in Grand Committee ? – see Column 407.

How indeed can spending all this parliamentary time be justified when those who benefits can be measured in the low thousands ?

Annex 7

Roll call of pro-homosexual events & legislation, by year (abbreviated)

1984 Chris Smith, newly elected to the UK parliament declares: “My name is Chris Smith. I’m the Labour MP for Islington South and Finsbury, and I’m gay“,

1989 The campaign group Stonewall UK is set up to oppose Section 28 and other barriers to equality

1992 The first Pride Festival was held in Brighton

1997 Gay partners in UK were given equal immigration rights

1997 Angela Eagle, Labour MP for Wallasey, becomes the first MP to come out voluntarily as a lesbian (not to be confused with Angela Mason (b Aug 1944), former civil servant & director of the gay rights lobby group Stonewall, aka Angela Weir, who advised Gov’t Depts on equality matters but who was put on trial for terrorism and bomb making in the 1970s.

1999 Stephen Twigg became the first openly gay politician to be elected to the House of Commons. Michael Cashman became the first openly gay UK member elected to the European Parliament.

2000 The Labour government scraps the policy of barring homosexuals from the armed forces

2002 Same-sex couples are granted equal rights to adopt

2003 Section 28, which banned councils and schools from intentionally promoting homosexuality, is repealed in England & Wales and Northern Ireland.

2004 The Civil Partnership Act 2004 is passed by the Labour Government (but nothing for heterosexuals).

2006 The Equality Act 2006 which establishes the Equality and Human Rights Commission (CEHR) and makes discrimination against lesbians and gay men in such provision as goods and services illegal (but nothing for heterosexuals).

2006 Section 28 successfully repealed.

2007 The Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations becomes law

2008 Treatment of lesbian parents and their children is equalized in the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008.

2010 Pope Benedict XVI condemns British equality legislation for running contrary to “natural law” as he confirmed his first visit to the UK.

2013 The coalition government unveils its Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill

E N D

REFERENCES:

- ‘Married but for all the wrong reasons’, http://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/39/

- British Social Attitudes Surve

- Children Act 2004

- Civil Partnership Act 2004

- Local Government Act 2003

- “Same-sex marriages – Canada’s hidden data” https://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/08/13/43/

- “Gay Marriage & Unions – an Inter-European Comparison” https://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/06/10/41/

- “Same-Sex Unions and Divorce Risk: Data From Sweden” http://www.breakpoint.org/search-library/search?view=searchdetail&id=2781

- Joanna Radbord, ‘Journal of the Assoc. for Research on Mothering’

- Margaret Hodge http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stemcor

- Also http://www.marriagedebate.com/pdf/SSdivorcerisk.pdf

- http://www.taeterinnen.org/en/02_impact.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divorce_of_same-sex_couples

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Section_28

Footnotes:

[1] LGBT – the commonly used initials for a rainbow alliance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender orientation.

[2] ‘Gay Britain: inside the ONS statistics’, Sept 23rd 2011, http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2010/sep/23/gay-britain-ons

[3] See for example, Law Commission paper on cohabiting proposals which favour wealth transfers to female cohabitees only when separating but not male cohabitees, and “Be Careful Who You Marry’ by Stephen Baskerville, Ph.D https://cohabitationlaw.wordpress.com/2015/02/16/16/

[4] For modern intolerance see also blog site http://www.glennbeck.com/2015/03/17/the-tolerant-left-turns-on-famous-gay-designers-because-of-their-comments-on-parenting/

[5] For example, contrary to its own Review in May 2002, the Blair government announced plans to legalise adoption by homosexuals and heterosexuals who ‘live together’.

[6] For example: Angela Mason a former director of Stonewall became director of Equalities Office from 2003 to 2007, even though a convicted in the 1970s as a member of the Angry Brigade bombing squad (see Annex 5) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Angry_Brigade ). And minister for Wales, Ron Davies, “moment of madness” in the bushes on Clapham Common, South London, in 1998.

[7] “ . . . veteran feminist Patricia Hewitt, who despite being married herself said a year before Labour’s 1997 victory that marriage ‘doesn’t fit any longer, particularly not in Britain’.”, by Melanie Phillips, June 2003 http://www.melaniephillips.com/marriage-lite-anyhow-sex-and-the-biological-bazaar

[8] Quote “. . . fulfilling a long-standing political promise to the Gay community.” see 2004 ONS report into same-sex union numbers https://motoristmatters.wordpress.com/2013/06/10/41/ .

[9] Gay and Lesbian couples; “Nearly a third of all the civil partners who ended their partnership last year were women under 40.” http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2450444/Gay-marriage-Civil-partnership-break-ups-approach-heterosexual-rate.html#ixzz3VXeMaPBW Oct 2013.

[10] “Mother loses her children to former lesbian partner,” by Frances Gibb, Legal Editor The Times , April 7, 2006 http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/law/article702829.ece .

[11] Hansard http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200304/cmhansrd/vo041012/debtext/41012-26.htm

[12] See http://www.guardian.co.uk/theobserver/2002/feb/03/features.magazine27 Sunday 3 February 2002

[13] She was a founding member and President of the Board of Directors of Daybreak, a refuge and multi-service agency for battered women and their children in the USA from 1977 – 1981. It is believed she unsuccessfully brought sex offence charges against her college lecturer when in Florida

[14] See “Marriage lite, anyhow sex and the biological bazaar”, By Melanie Phillips, Daily Mail, June 30 2003. http://www.melaniephillips.com/

[15] See http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2565352/Apologists-paedophilia-As-Mail-exposes-links-senior-Labour-figures-vile-paedophile-group-one-man-abused-child-asks-wont-admit-wrong.html

[16] See http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2831219/Government-gave-money-Paedophile-Information-Exchange-group-says-Home-Office-whistleblower.html

[17] See http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/april/9/newsid_2523000/2523609.stm

[18]http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/about-ons/business-transparency/freedom-of-information/what-can-i-request/previous-foi-requests/population/number-of-civil-partnership-dissolutions/index.html See also http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob2/civil-partnership-statistics–united-kingdom/2012/rtd-dissolutions.xls (Table 1)

Broken Homes – a silent conspiracy ?

A truth that dare not speak its name

More than 12 years on from this Jan 2003 report the public is still not allowed to know the full damage done to families and society by legislation that encourages divorce.

Nor is the public allowed to appreciate the very real and graver disadvantages many children have to struggle with as a consequence. These children are blissfully unaware that their futures and life chances have been brutally compromised by their parents’ actions and that they will never perform or aspire to their full potential.

Study Says Broken Homes Harm Kids More

by Sue Chan, Jan 23rd 2003

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/broken-homes-broken-children/

CBS/AP (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Children growing up in single-parent families are twice as likely as their counterparts to develop serious psychiatric illnesses and addictions later in life, according to an important new study.

Researchers have for years debated whether children from broken homes bounce back or whether they are more likely than kids whose parents stay together to develop serious emotional problems.

Experts say the latest study, published this week in The Lancet medical journal, is important mainly because of its unprecedented scale and follow-up – it tracked about 1 million children for a decade, into their mid-20s.

The question of why and how those children end up with such problems remains unanswered. The study suggests that financial hardship may play a role, but other experts say the research also supports the view that quality of parenting could be a factor.

The study used the Swedish national registries, which cover almost the entire population and contain extensive socio-economic and health information. Children were considered to be living in a single-parent household if they were living with the same single adult in both the 1985 and 1990 housing census. That could have been the result of divorce, separation, death of a parent, out of wedlock birth, guardianship or other reasons.

About 60,000 were living with their mother and about 5,500 with their father. There were 921,257 living with both parents. The children were aged between 6 and 18 at the start of the study, with half already in their teens.

The scientists found that children with single parents were twice as likely as the others to develop a psychiatric illness such as severe depression or schizophrenia, to kill themselves or attempt suicide, and to develop an alcohol-related disease.

Girls were three times more likely to become drug addicts if they lived with a sole parent, and boys were four times more likely.

The researchers concluded that financial hardship, which they defined as renting rather than owning a home and as being on welfare, made a big difference.

However, other experts questioned the financial influence, saying Swedish single mothers are not poor when compared with those in other countries, and suggested that quality of parenting could also be a factor.

Commenting on the results, Sara McLanahan, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University, and who was not involved in the study said:

- It makes you think that what you’re seeing is just the most dysfunctional families having these problems, rather than the low income. The money is really an indicator of something else.

- If you really thought that it was the income that makes the difference, you would think that Swedish lone mothers would do a lot better than the British or those in the U.S., but they look very similar.

Other experts agreed.

In the last 20 to 30 years, poverty has been greatly reduced everywhere in Europe, but psychiatric problems in children have not, said Dr. Stephen Scott, a child health and behavior researcher at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, who also was not involved in the study.

He said that in previous studies, once researchers have adjusted their results to eliminate the influence of bad parenting, any increased risk of emotional problems shrinks markedly. This, he said, indicates it is not so much single parenthood but the quality of parenting that is at issue.

- The kind of people who end up as single parents might not have done well by their kids, even if they hadn’t ended up alone. They tend to be more critical in their relationships, more derogatory toward other people.

Scott added that it is also harder to be a warm, non-critical parent when you’re bringing up a child alone. However, he noted that there are plenty of children from single-parent families who don’t end up with serious emotional problems.

There may also be a genetic element: More irritable people are more likely to become separated, but they are also more likely, whether they are separated or not, to have more irritable children, Scott said.

McLanahan was reported as saying:

- The whole field is highly debated. This is another piece in that debate that makes several important points – firstly that there really is an increased risk in young adulthood of pretty bad things. It also indicates it’s not all about the money, but may be about the people themselves,”

E N D

——–

Reference:

- The Lancet, http://www.thelancet.com

- “Mortality, severe morbidity, and injury in children living with single parents in Sweden: a population-based study” by Gunilla Ringbäck Weitoft, Anders Hjern, Bengt Haglund, Måns Rosén (http://www.thelancet.com/journal/journal.isa ). Centre for Epidemiology, National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm, Sweden (G R Weitoft BA, A Hjern MD, B Haglund DMSc, M Rosén PhD); Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University, Sweden (G R Weitoft, M Rosén); Department of Clinical Sciences, Huddinge University Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden (A Hjern).

Dads & babies – society’s curious double standard

Can single Dads handle the night shifts with their babies ?

By Richard Warshak

first published in The Institute for Family Studies

http://family-studies.org/can-single-dads-handle-night-shifts-with-their-babies/

Fifty-one years ago, The Feminine Mystique ushered in the movement that promised to liberate parents from the cultural straitjacket of rigid gender roles. We asked fathers to be more than just material providers to their children. Stop pacing the maternity ward waiting room and join your wife in the delivery room. Help pay for diapers, formula, and children’s books, yes. But don’t expect Mom to change all the diapers, do all the feeding, and read all the bedtime stories.

Dads got the message. The most recent study of dual-earner families reported that on a typical workday, fathers spent a little more than 1.5 hours directly engaged with their three-month-old infants. This may not sound like a lot, but it amounts to 41 percent of the total time that the two parents interacted with their infants. Not quite half. But getting there. And babies are benefiting from all this time with Dads.

Whether observed in the laboratory or in natural settings, Dads demonstrate over and over that their presence matters a great deal to their children from the baby’s birth onward. The more time parents spend with their infants and toddlers, the better able they are to read their baby’s signals and respond sensitively to their children’s needs. It takes nothing away from mother-child relationships when Dads change diapers and bathe babies. For some important areas of development, such as vocabulary and children’s persistence in the face of obstacles and frustration—the “can-do” attitudes that are essential to success in life – fathers may have a greater impact than do mothers.

When it comes to encouraging hands-on shared parenting, society imposes a curious double standard.

All this is good news for children in two-parent homes. But not such good news for children whose parents separate. When it comes to encouraging hands-on shared parenting, society imposes a curious double standard. When they live with their children’s mother, we expect Dads to assume their fair share of parenting responsibility. When parents separate, though, some people think that young children need to spend every night in one home, usually with mom, even when this means losing the care their father has been giving them.

In her recent Family Studies blog post, Professor Linda Nielsen showed how this idea arose from seriously flawed interpretations of data that were repeated often enough to acquire the aura of truth. Just last month a popular United Kingdom authority on parenting relied on such interpretations to conclude:

- “Findings strongly suggest that shared care that includes spending nights, or even a single night at a time, away from ‘home’ and mother is seldom in the best interests of children under around four years of age irrespective of the families’ socio-economic background, their parenting or the co-operation between the parents.”

Many of us still think that it is Mom’s exclusive role to care for infants and toddlers, and that we jeopardize young children’s well-being if we trust fathers to do the job.

Where does science stand on these issues? To find out, I spent two years reviewing the relevant scientific literature and vetting my analyses with an international group of experts in the fields of early child development and divorce. The American Psychological Association published the resulting consensus report with the endorsement of 110 of the world’s leading researchers and practitioners. One of the signatories was UVA’s Emerita Professor of Psychology E. Mavis Hetherington.

Shared parenting should be the norm for children of all ages whose parents live apart from each other.

We reached two main conclusions. First, the social science evidence on how healthy parent-child relationships normally develop, and the long-term benefits of those relationships, supports the view that shared parenting should be the norm for children of all ages, including very young children, whose parents live apart from each other. Second, restricting fathering time to daytime hours until children enter kindergarten is not the best arrangement for most children if we want to give them the best chance for normal relationships with their fathers. Naturally, shared parenting is not for all families. In general, though, we favor having young children spending some nights at their fathers’ homes, and find no reason to postpone overnights until children turn four.

It is time to resolve our ambivalence and contradictory ideas about fathers’ and mothers’ roles in their children’s lives. If we value Dad reading Goodnight Moon to his toddler and soothing his fretful baby at 3 a.m. while the parents are living together, why withdraw our support and deprive the child of these expressions of fatherly love just because the parents no longer live together, or just because the sun has gone down ?

Richard A. Warshak is a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. He is the author of “Social Science and Parenting Plans for Young Children: A Consensus Report,” published in Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, Divorce Poison: How To Protect Your Family From Bad-mouthing and Brainwashing, and Welcome Back, Pluto: Understanding, Preventing, and Overcoming Parental Alienation.

E N D

Alaska & Arizona get an “A”

Today we learn that another set of Shared Parenting initiatives across the US have failed – see, “Report: States fail on shared parenting laws” by Jonathan Ellis (‘USA TODAY’, Nov 13th). [1]

The report compiled by the National Parents Organization – and shown below – grades each state on its capacity to deal with shared parenting as a child custody alternative (see Appendix 1)

The top scoring states were Alaska and Arizona with ‘B+’ grades, and seven states plus Washington, DC, received a ‘B’ grade. Nearly half of the 50 states received a ‘D’ grade but New York and Rhode Island rated only a poor ‘F’.

This reluctance is typical of the ingrained attitude of governments afraid of any progressive thinking that they haven’t thought of first. It is the general fate – with notable exceptions – that greets any supporter of shared parenting (though it has to be said that the situation is improving by the year and had they been undertaken 10 years ago, in 2004, then firstly it would not have made headlines and secondly, the grades would all have been ‘F’). At least today the subject has now become part of mainstream culture.

The struggle for recognition is reminiscent of barriers to progress faced by mathematician and electronics inventor Ivor Catt (you can thank him for his part in making it possible for the computer you are now using to handle data). In a lecture given to the Ethical Society, entitled “The Politics of Knowledge” (24th March 1996), Catt spelt out the difficulties of 1/. acceptance and 2/. of suppression that inventors have faced through the ages (see Appendix 2). In a separate essay (“The Clever Take the Brilliant”), Catt outlined how one doesn’t have to be the sharpest tool in the box to ‘win out.’ It’s comparable to fitting one dud spark plug to a car engine and despite the finest and most perfect performance from all the other spark plugs, the engine’s perfomance drops and the engine is in effect governed by the dullest speak plug.

While sole mother custody is the predominant regime most often found, the custody engine and children’s safety will always, despite everyone’s best endeavours, be performing at below par. Linda Scher, mentioned below typifies the schism in thinking and the inability to think outside the box. She confuses the shared parenting concept as a simplistic choice between 1/. promoting parental rights versus 2/. children’s needs. She then further muddies the waters by stating that ” . . . judges need flexibility to determine custody issues on a case-by-case basis” completion ignoring that at present custody is decided on nothing better than a conveyor belt basis.

‘Report: States fail on shared parenting laws’

Jonathan Ellis, USA TODAY, November 13, 2014

Supporters of shared parenting for children whose parents are divorced or separated have few victories to claim in their attempts to win family law reforms across the country

- “It’s been a hard slog, and there’s not a lot to show for those efforts,” said Dr. Ned Holstein, the founder of the National Parents Organization.

Holstein’s organization and other supporters are trying to reverse decades of family law tradition where judges often award custody to one parent – typically the mother – while the non-custodial parents receive less time with their children. In cases that don’t involve allegations of physical abuse, substance abuse or other issues, supporters argue that both parents should have a 50-50 split with children.

But the difficulty in convincing state lawmakers to buck tradition was reflected in a first-ever report card released Thursday by the National Parents Organization. The study evaluated state custody laws and found that most of them are not friendly to shared parenting.

Nearly half the states received a D, while New York and Rhode Island received Fs. No state received an A, but seven states and the District of Columbia received a B. The top scoring states were Alaska and Arizona.

Holstein said judges across the country still rely on decades-old research rooted in Freudian psychoanalysis about what’s best for children. More recent studies have discredited theories that children should only be with their mothers, he said.

Linda Nielsen, a professor of adolescent and educational psychology at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, agrees. Nielsen has reviewed dozens of studies comparing children who had one custodial parent with children in shared parenting situations. Children in shared parenting situations had lower levels of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, truancy and other negative behaviors than children who lived primarily with a custodial parent, she said.

Nielsen said that judges, lawyers, psychologists, mediators and others who work in family law are often unaware of the research supporting shared parenting.

- “We’ve done a very poor job of getting the data to those people,” she said. “That’s the fault of social scientists.”

Despite research showing otherwise, many people believe that mothers are better parents than fathers, Nielsen said.

- “It’s almost one of those issues where people don’t want to look at the research because they have those gut feelings,” she said.

But Linda Scher, a family mediator in Portland, Ore., said judges need flexibility to determine custody issues on a case-by-case basis. She notes that within family law, there is an ongoing battle between those promoting parental rights versus children’s needs.

Shared parenting works well in the right situations, she said. But not necessarily for children who are very young, or for those who need consistency.

- “You have to look at a menu of factors,” said Scher, who serves as the chair of the Parental Involvement Work Group of the Oregon State Family Law Advisory Committee.

Ultimately, she added, the law in Oregon doesn’t weigh in on whether shared parenting is a good or bad idea.

- “The parents are in the best position to make that call,” she said.

Despite limited success in legislatures, Holstein said supporters plan to focus efforts in 2015 on legislation that would require judges to consider shared parenting when issuing temporary orders. Those orders are the first step in a divorce proceeding in which a judge establishes initial custody and makes other orders regarding money and living arrangements for the separating couple.

Parenting, Holstein said, is a constitutionally protected practice, and judges who issue temporary orders often know nothing about the couple or about what’s in a child’s best interest.

- “How can a court honestly declare that they are fashioning something in the best interest of a child when they don’t know the child? They can’t. It cannot be done by definition. Here’s a newly divorcing couple walking into the courtroom, but you know nothing about them,” he said.

And absent changes in family law, Holstein said he can envision a court challenge arguing that parents are being deprived of their constitutional rights to be parents.

E N D

Appendix 1

Compared to some geographical and political blocs the US could be said to be galloping ahead in the Shared Parenting(SP) stakes. Of course, the main difference is that those other geographical and political blocs are unitary nations and the US is a loose federation of semi-autonomous states. Consequently there is a great disparity between states while giving an encouraging if misleading average, thus:

- “Unfortunately, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 17% of children of separated or divorced parents have shared parenting, which prevents their ability to benefit equally from both parents and has a tremendous impact on their emotional, mental and physical health (see “A New Look at Child Welfare: Single Parenting Versus Shared Parenting”).

Compared with the rate of SP in Australia, Belgium, France (and certainly the UK), 17% is a very respectable rate.

Analysis by grades

- 0 states received an A

- 8 states received a B

- 18 states received a C

- 23 states received a D

- 2 states received an F [these were New York and Rhode Island]

National Parents Organization’s 2014 Shared Parenting Report Card is the first national study to provide a comprehensive ranking of the states on their child custody statutes, assessing them primarily on the degree to which they promote shared parenting after divorce or separation.

Single Parenting Vs Shared Parenting

The Centers for Disease Control, the Department of Justice, the Census Bureau and numerous researchers have reported alarming outcomes for the 35% of children who are raised by single parents. Yet, until now, this factor has been largely ignored in the conversation about child wellbeing. Children raised by single parents account for:

- 63% of teen suicides;

- 70% of juveniles in state-operated institutions;

- 71% of high school drop-outs;

- 75% of children in chemical abuse centers;

- 85% of those in prison;

- 85% of children who exhibit behavioral disorders; and

- 90% of homeless and runaway children

These figures and rates have been ‘standard’ in the US for approximately the past 30 years and there is no likelihood of them changing until SP is adopted more fully.

The question may arise as to just why Alaska and Arizona should represent such outstanding innovation and foresight and how SP is woven into their child custody regulations. The following points may answer some of those questions.

- Alaska explicitly permits shared custody “if shared custody is determined to be in the best interest of the child.” ALASKA STAT. § 25.20.070

- Alaska requires that, in issuing temporary orders, “[u]nless it is shown to be detrimental to the welfare of the child … or unless the presumption under ALASKA STAT. § 25.24.150(g) is present, the child shall have, to the greatest degree practical, equal access to both parents during the time that the court considers an award of custody.” ALASKA STAT. § 25.20.070

- Alaska statutes require, except in cases of domestic abuse, consideration of a “friendly parent” factor: “the willingness and ability of each parent to facilitate and encourage a close and continuing relationship between the other parent and the child.” ALASKA STAT. § 25.24.150(c)(6)

- Arizona requires courts to “adopt a parenting plan that provides for both parents to share legal decision-making regarding their child and that maximizes their respective parenting time.” ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 25-403.02

- Arizona explicitly endorses a “friendly parent” rule. ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 25-403

- Arizona explicitly requires courts to consider “[w]hether one parent intentionally misled the court to cause an unnecessary delay, to increase the cost of litigation or to persuade the court to give a legal decision-making or a parenting time preference to that

Elsewhere in this series of blog sites we have reported on Florida’s earlier attempts to embrace SP. This is what the National Parents Organization’s 2014 Shared Parenting Report Card concluded for Florida:

- Florida has a strong statutory presumption of shared parental responsibility: “The court shall order that the parental responsibility for a minor child be shared by both parents unless the court finds that shared parental responsibility would be detrimental to the child.” FLA. STAT. § 61.13

Appendix 2

THE POLITICS OF KNOWLEDGE

Ivor Catt

Published in The Ethical Record, June 1996.

[Annotated version]

In a letter in Wireless World, Nov. 1981, J.L. Linsley Hood writes that “censorship has been effective throughout my own professional career….”. He lists nine authors who could not have been published anywhere else but in Wireless World.

There is usually no conspiracy to suppress heretical ideas. There is no need of one, except in some specific instances, because as Charles McCutcheon wrote in the New Scientist (itself a notorious suppressor, but not as bad as Nature) on 29 April 1976, p.225, “An evolved conspiracy” suffices.